News & Events

“Speak Count, it is your cue”, Beatrice, Much Ado About Nothing

“You are now out of your part”, Olivia, Twelfth Night

“As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put besides his part” Sonnet 23

Early modern plays are stuffed with references to lines, parts, prompts and cues. The figure of the book-holder shouting lines from the tiring-house also appears. Why, though? Were early modern players lazy or forgetful? Not at all! They were part of a truly astonishing theatre-producing machine, and their “parts” were part of it.

Actors were not given the full text for a play, or even for whole scenes – they were given their own lines only, with cues indicating when they were to speak. Actors had to rely on their own text preparation, their stagecraft skills, and simply listening and responding."

The cue-script technique made several things easier in this high-pressure, high-turnover environment: having your own lines only meant you could check them more quickly on the “roll” of parchment in your pocket, while time and money were saved on copying, and the chance of any unscrupulous printer boot-legging your play text for their own profit was reduced.

Parts were sparse on information for the player. Cues could be one or two words long, with no clue who was going to say them, and all they knew about the play and their character was in their lines: verse structure, prose, rhyme, poetic language (the stuff you learned at school). Early modern audiences would have seen players on stage listening literally for their lives, constantly alert to hear their cues, frequently caught out and surprised. Performances were vibrant and authentic, with actors responding instinctively. Gaps and calls for line were not a disruption, but part of the production. Audiences would pay double for a place at the first performance of a new play, with all the goofs and gaffes – they valued the unique edge-of the-seat energy and authenticity of these performances.

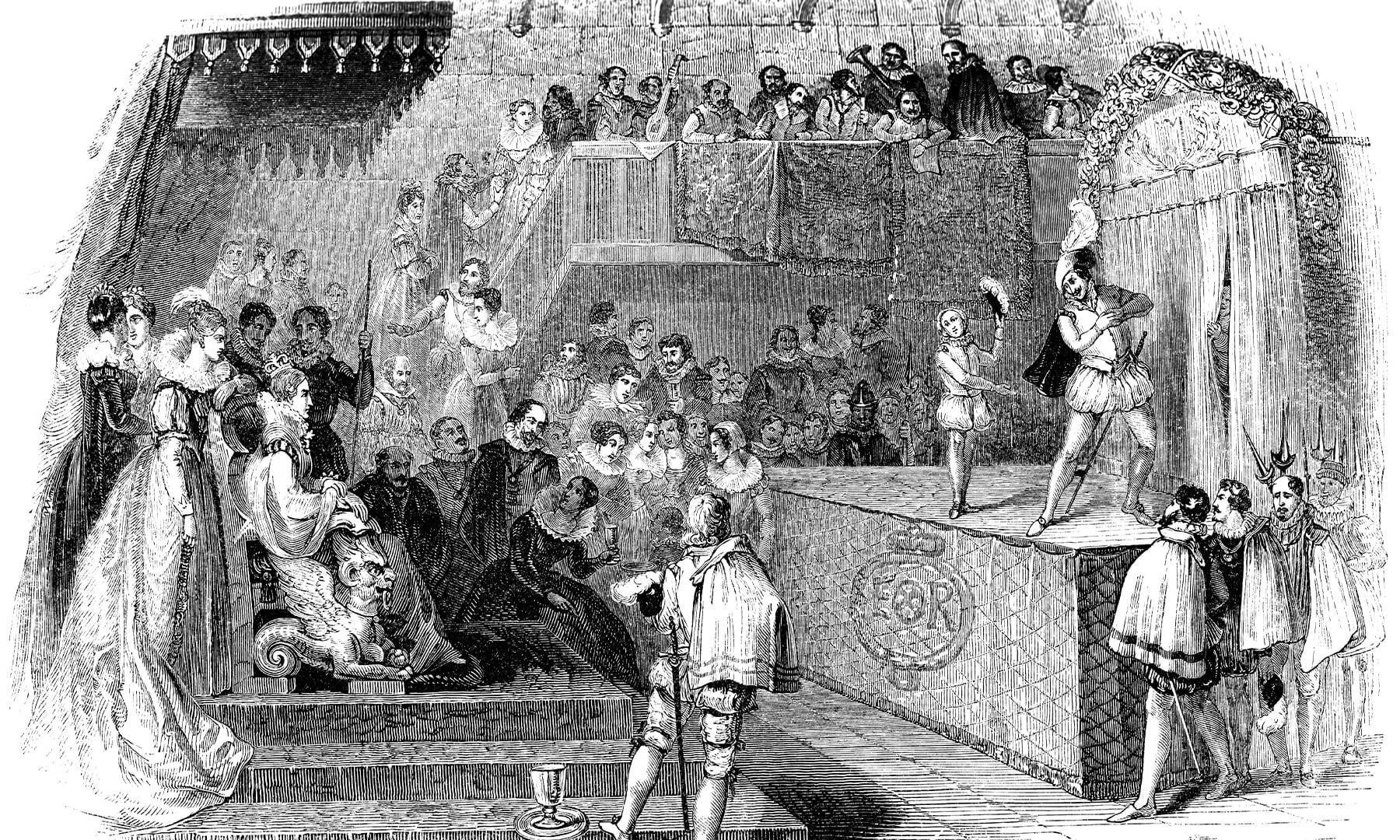

Playhouses staged a different play every day, six afternoons a week (weather and plague permitting) in the cut-throat battle for audience. Players held between thirty and forty “parts” in their head. Diary (1591-1609) by Phillip Henslowe, Manager of the Rose Playhouse shows thirty-six different plays staged in six weeks in 1595. Henslowe records costs of commissioning plays, costumes and repairs, but beyond the cost of wine for a preliminary read-through of a new play, there is absolutely no record of rehearsal rooms or rehearsal period pay for actors.

Come backstage at the Curtain. The actors coming off stage in the afternoon will be given out their parts for the next day’s play, which may have been on recently, or have not been performed for months. They need to review their lines, or learn new ones following changes in casting. The most likely time for learning is the next morning, with a fresher head and better (free) daylight to read by. By midday they’re at the playhouse, running through any scenes, then off to the tiring house to bag the best costume, have lunch, and go on at 2pm and perform.

With no rehearsals, plays only burst into existence on the stage, in front of the audience. Costumes helped to make it clear who was who on the stage, but beyond that, it was down to the actors’ storytelling skill alone.

As a 21st Century cue-script practitioner, I use the same system to prepare my (very brave) actors. To have had the opportunity to perform at the open stage night, at the site of the Curtain, and to have been able to bring cue-script performance home, was one of the greatest honours of my life.